When we were children we used to paint and draw with pleasure and delight. For a few short blissful years we could do no wrong with our paints and crayons – we were free to explore, imagine and create. Then we began to be taught what was “good” and “bad” in art: those of us who were “good” at art started trying to perfect our skills while those of us who were not “artistic” simply threw away our paintbrushes. And that, say the art therapists, is a crying shame. Uninhibited art, they explain, has the power to heal: it offers a clear, straightforward route to the unconscious, to the hidden depths of our psyche. Rediscover the joy of art and you could put yourself back in touch with repressed emotions and long-buried hurts. You could even start up a conversation with your very soul.

When we were children we used to paint and draw with pleasure and delight. For a few short blissful years we could do no wrong with our paints and crayons – we were free to explore, imagine and create. Then we began to be taught what was “good” and “bad” in art: those of us who were “good” at art started trying to perfect our skills while those of us who were not “artistic” simply threw away our paintbrushes. And that, say the art therapists, is a crying shame. Uninhibited art, they explain, has the power to heal: it offers a clear, straightforward route to the unconscious, to the hidden depths of our psyche. Rediscover the joy of art and you could put yourself back in touch with repressed emotions and long-buried hurts. You could even start up a conversation with your very soul.

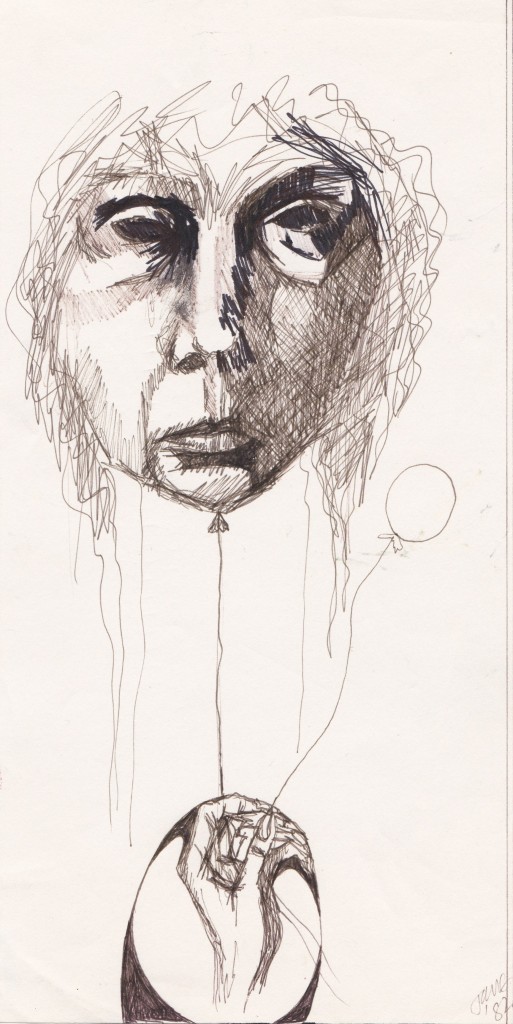

Art therapy is most definitely not about painting or drawing “properly” – the aim is not to make pretty or lifelike pictures but rather to let go of any expectations and simply see what happens. Art therapy is like a key to a secret language of the psyche. Paint and you could discover different sides to your personality; you could gain confidence and self-esteem; you might even find quite physical ailments disappear when you allow yourself a creative outlet.

Art has been used as a therapeutic tool for many years. Back in 1810 a German psychiatrist Johann Christian Reill positively encouraged his patients to paint. His colleagues thought it was a way of diverting them from their problems but he insisted it was rather an attempt to put them in touch with their “passions”, their inner desires, hurts and fears. Since that time many psychiatrists and psychoanalysts have discovered that when people paint freely they are able to express feelings and give a form to fears and terrors on paper that they are quite unable to express in words. Art as therapy is, quite simply, a direct way of communicating with the unconscious.

Since those early days art therapy has become well established in the NHS where it is often used to help those who are mentally or terminally ill, people who have been abused or who are addicted to drugs. It can be a wonderful tool to communicate with children with special needs and adults who find it difficult to talk about their feelings. But it is becoming increasingly popular amongst people with less pressing needs. Workshops are springing up around the country and more art therapists are starting to work with individuals on a private basis. Some people simply enjoy painting without the pressure of having to produce a masterpiece; others find it a wonderful way to relax. Yet more regard it as a serious tool for sorting out their lives: a way to look at problems or fears in a safe, controlled environment. Everyone, it appears, can benefit from holding a paintbrush and splashing paint.

I hadn’t painted since I left school and so it was with a certain amount of trepidation that I made my way to The Pelican Centre, a rambling medieval house in a small Somerset village which used to host a weekly art therapy group plus frequent residential weekend workshops (sadly it is no longer operational). About twenty of us gathered, plied with coffee, in a comfortable room full of armchairs. Michael Edwards, a Jungian analyst and art therapist who was running the weekend, immediately put the most paint-phobic at ease. “I’m not asking for any skills,” he insisted, “you can’t make a mistake; you simply can’t do it wrong. Nobody has to know what your pictures are or mean – you are only answerable to yourself.”

Although many art therapists will allow you a totally free rein, to paint whatever you choose, he had chosen the fairy tale of Sleeping Beauty as a rough theme for the weekend. For some time we discussed the symbols and themes of the tale. “Fairy tales pick up the deep truths of life,” he explained, “however painful, uncomfortable and impossible they may be – they touch the deep roots of life.” We talked about the many versions of this ancient tale, including its less well-known and vastly more sinister versions (full of child-eating ogres and grisly suicides) that Disney carefully chose to ignore. Then it was time to paint.

The art studio with its smell of paints and crayons brought back a flood of school-time memories. “Find a comfortable place,” urged Edwards, “you might want to hide in a corner – that’s fine. Sit and think quietly before you begin and let the story work on you. See what comes up. It might dimly connect to your life; you might just enjoy the images. Let them come.” I sat and stared at my blank sheet of paper with something approaching horror: it felt like looking at an exam paper and not knowing any of the answers. Then, slowly, I started tentatively to paint. It began as a representation of Sleeping Beauty – asleep amidst the briars. Then I found the paints I chose getting darker and darker, the paint strokes more and more harsh. “She’s not asleep – she’s dead,” I found myself thinking and almost burst into tears as thoughts of my grandmother’s recent death came flooding back into my mind. Fear, sorrow, pain, hurt, a bleak sense of mortality all poured out onto the paper. As if by sixth sense, Michael Edwards appeared at my shoulder and talked quietly and calmly before urging me to start painting again on a fresh sheet.

At the end of the day we all paused and assessed our work. “Try talking to your pictures,” urged Edwards to the group, “you might write a commentary or simply scribble a letter to your painting. Ask it questions: it might answer. I know it sounds nuts but it does seem to work.” “My picture said I needed a rest,” laughed one woman and added, “I think I’ll take its advice.” Another said, “I felt my picture had no point to it but then I thought why does everything have to have a point? I decided I could have time in my week where there didn’t have to be a point.” Some people chose not to say a word – nobody was pushed.

“Art leads people gently into their psyches,” says Edwards, “sometimes distressing things come up but somehow they can be contained by the paper. You might feel at the mercy of a nightmare or a fantasy but by putting it in a picture it becomes objectified. And you always have a choice, you can put that unconscious world, however distressing, away in a drawer.” In other words, art can give you back an element of control over your unconscious mind. Edwards is loath to claim the miraculous for his therapy but sometimes, he grudgingly admits, people even find physical problems disappear. One woman had suffered for years from a frozen shoulder: once she started painting, the shoulder cleared up almost instantly. “You can’t count on it, but yes it does happen,” he says, “I wouldn’t say come to art therapy and get rid of your rheumatism but it does happen.”

But most people don’t seek out art therapy as a cure for physical aches and pains. Rather they see it as a journey into the recesses of their own minds. And like a voyage over uncharted seas, no-one quite knows what they will find. It might be frightening, full of terrors or it might uncover hidden strengths and talents, new resources and strategies. Quite likely it will do both. I left the Pelican Centre with an armful of paintings, feeling very small, sad and vulnerable. As I drove home I quietly grizzled, realising that I still had not given myself permission to fully grieve. Back in the safety of my own kitchen, I allowed myself to let go and really cry. I sobbed for about three hours and emerged with red-rimmed eyes and a mascara-smudged face. From the outside I looked terrible but inside I felt 100 percent better.

Try it yourself: Paint your Lifetime

To get a feel for art therapy try this exercise from the book Inward Journey: Art as Therapy by Margaret Frings Keyes (Open Court).

* Take a large piece of paper and any art materials you choose (paints, crayons, felt tip pen). Imagine that the paper represents your lifetime – the beginning, the now, the future and the end. * Sit quietly for a few moments and then fill it as you choose. Don’t expect anything or try to draw “properly”, use whatever symbols or images you feel appropriate. You might choose to depict events in your life or simply choose different colours to represent different parts of your life or feelings.

* When you have finished, be aware of how you feel – both in your mind and your body. What is your painting saying – does it show more about how you think or how you feel about your life? What are the themes and questions in it?

* Don’t throw it away afterwards – keep it and look at it from time to time to see if any new insights appear.

A version of this first appeared in the Daily Mail.